ARGO

DEPTH: 44 - 50 m

SKILL: Expert

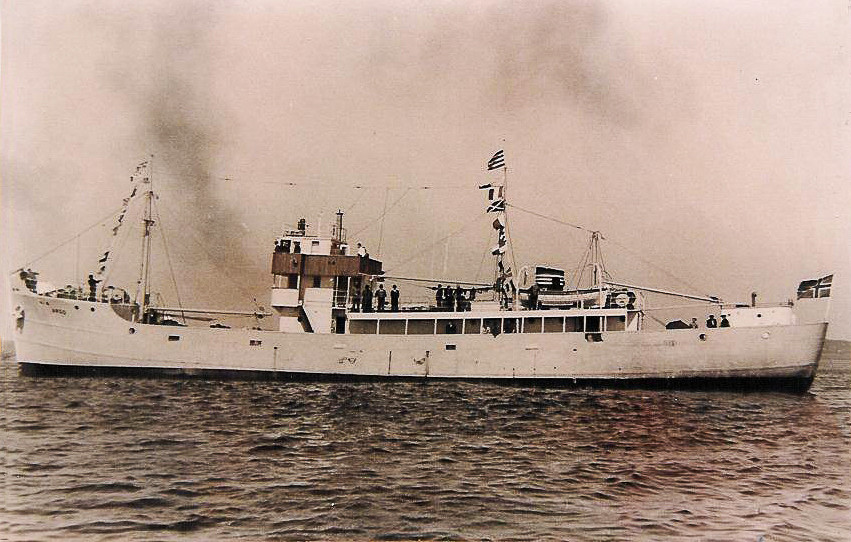

Argo (ex-HMS Flint); motor ship - refrigerator; Norwegian, Valdemar Skogland company from Haugesund

Built: July 1942

Sunk: 27th January 1948 (navigational error – hit a mine)

Dimensions: l=52 m, w=7 m, h=4.5 m

Coordinates: 44.86908° N, 14.20048° E (bow) , 44.86937° N, 14.20102° E (stern)

Location: about 5 nm E of Cape of Crna Punta

Access: 2/5 access is solely by boat (the location is in the open sea)

Visibility: 3/5 very variable, occasionally very good visibility

Current: 3/5 moderate, occasionally strong

Flora and fauna: 5/5 varied life on and around the wreck, on the wreck large specimens of fish

HISTORY:

The HMS Flint belonged to a group of warships – minesweepers, which after the Second World War the British government sold to Norwegian ship owners. So the Norwegian ship owner Valdemar Skogland from Haugesund bought four disarmed British Isles class minesweepers with the intention of partitioning them into cargo ships. One of these decommissioned minesweepers was built in Quebec, Canada in July 1942 and delivered to the British Navy as the HMS Flint. The renovated ship gained a new name – Argo (international call sign LLOR) and in May 1947 it entered service in the fleet of Skogland’s company. On 30th December 1947, the Argo and its 12 crew members sailed out from Haugesund with a cargo of frozen cod for the long journey to Venice. Arriving safely at its destination, in Venice it unloaded the cod, and was loaded with various vegetables, mainly tomatoes for a new destination – Rijeka, where it would then pick up a cargo of quality wood bound for Oslo. Sailing out from Venice on 26th January 1948, the Argo took a course towards Cape Kamenjak at the southern end of Istria.

At about 2000 hrs. the Argo dropped anchor in a cove near Cape Kamenjak. There was a moderate “jugo” (pronounced “yugo”) wind, and visibility was poor. They spent the night there, because the commander did not dare to sail into Kvarner by night due to the fear of mines. At that time, left over from the Second World War, there were still many minefields in the Adriatic uncleared, especially on the outskirts of Kvarner. Only a few safe navigational corridors were marked with buoys which were not equipped with lights.

The following morning at 0730 hrs. the Argo pulled up its anchor and with a moderate southerly wind continued its journey towards Kvarner. Commander Sigvald Svendsbø decided to continue the journey alone trusting in the sea charts, the instructions for sailing into Kvarnerić and the buoys which marked the navigational corridor. However the commander did not know the fact that many of the buoys had disappeared after being detached after several frequent winter storms. The “jugo” wind continually strengthened, reaching storm force around noon. Visibility was becoming worse.

Just before 1230 hrs. the ship shook with a tremendous explosion and it seemed that the ship broke up and immediately began to sink. When the crew surfaced, there was no trace of the ship. Foam from the refrigeration insulation system was floating all over the surface, obscuring their view. The surviving crew members desperately fought for their lives. Smoke was all around them, and the poisonous gas from the refrigeration system stung their eyes which almost poisoned them. The only option was to swim downwind. After some time they split up. Mikalsen had swum into the cove of Vošćice east of the settlement of Koromačno, on the eastern coast of Istria. When he came round, he saw a light from a nearby house. Early in the morning the police and inhabitants began to search the shore for survivors. They only found small remains of the ship, between which the lifeless bodies of the helmsman Hovland and the sailor Vikingstad were floating.

WRECK CONDITION AND DIVING:

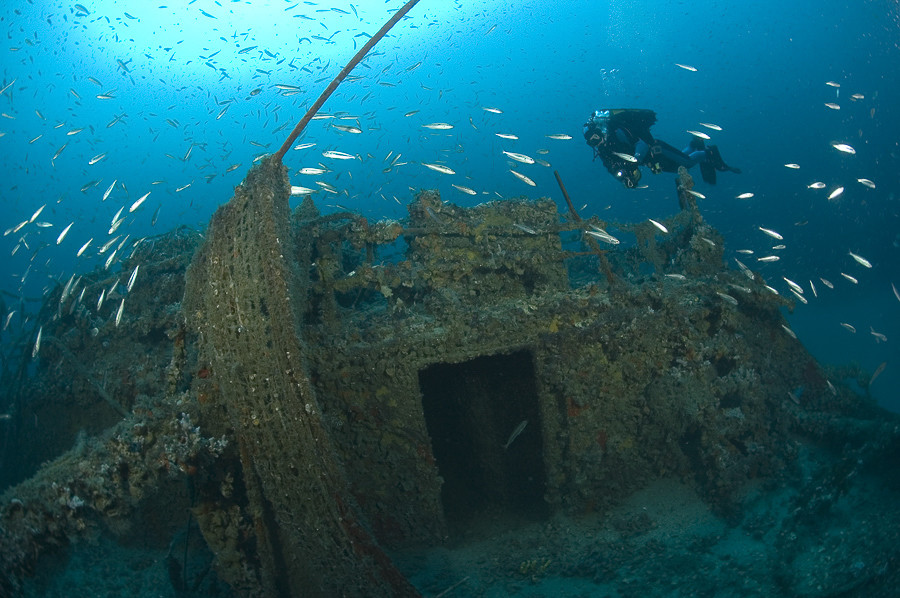

The wreck of the Argo is split into two in the middle. The two parts detached from each other, and both parts lie on the bottom in an upright position. They are connected by a rope so that in poor visibility it is possible to swim from one part of the ship to the other. Visibility depends on the season and daily conditions, and even on the time of day.

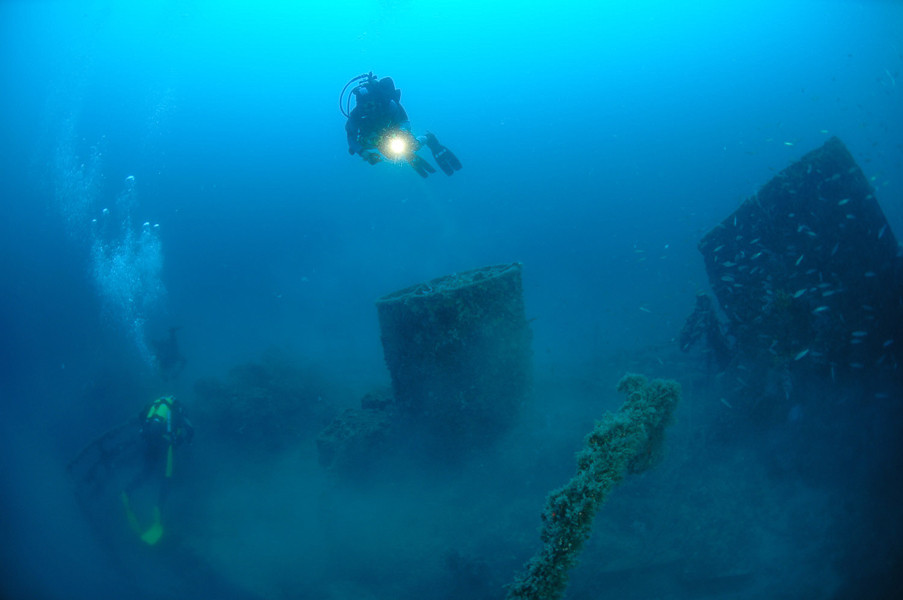

As the location is in the open sea the wreck can only be located with the help of GPS equipment and a good echo sounder. Visibility can be quite poor under the surface – in the summer months a murky warm layer of sea may extend down to ten or so metres deep. However visibility in the lower layers is most frequently better. Passing thirty metres the visibility suddenly begins to improve.

Floating above the forecastle we can observe the anchor gear and chains which lead towards the holes in the deck. The anchors are still in place on both sides of the bow. From the forecastle steps lead down to the main deck. On it can be seen the dark opening of the forward cargo hold. Immediately behind the opening is the base of the mast which lies broken next to the wreck. After less than three metres in the direction of the stern, the superstructure and hull suddenly stop – it looks as though some giant had torn away the rest of the ship! At the point of the break the thick plating is torn and twisted in all directions as though it was made of paper. Underneath the deck here it is possible to carefully enter the interior of the ship and there is enough space to pass all the way to the forward cargo hold.

Following the rope we come to the second part of the wreck, about fifty metres away. The rope is tied to the very end of the stern, right next to a small aft superstructure. Passing around the elegantly curved stern we can look for the propeller and rudder blade, however a murky layer of seawater often hangs close to the silty or sandy seabed. Returning to the aft deck and swimming further, we come across the dark opening of the rear cargo hold, and a little further is the rest of the superstructure on the sides of which are attached the davits for the lifeboats. In front of the funnel rectangular upper windows can be seen which served as ventilation for the engine room, some of which are open. Just a few metres further and this section of the wreck abruptly ends at the torn panelling and split hull. At this point for several metres part of the deck is very bent upwards, looking exactly like an opened can of tuna. At the point of the break is looks as though one can peek into the interior, but due to the amount of debris of various pipes, wires and metal plating it is not recommended to linger too long.

The safest way to end the dive and return to the surface is by going back to the part of the ship where the rope is tied, which is also handy to hold on to when the current can be quite strong, whilst we need to perform decompression.

The description and illustrations are a courtesy of Danijel Frka and Jasen Mesić. Buy the whole book here: https://shop.naklada-val.hr/product_info.php?products_id=561

Built: July 1942

Sunk: 27th January 1948 (navigational error – hit a mine)

Dimensions: l=52 m, w=7 m, h=4.5 m

Coordinates: 44.86908° N, 14.20048° E (bow) , 44.86937° N, 14.20102° E (stern)

Location: about 5 nm E of Cape of Crna Punta

Access: 2/5 access is solely by boat (the location is in the open sea)

Visibility: 3/5 very variable, occasionally very good visibility

Current: 3/5 moderate, occasionally strong

Flora and fauna: 5/5 varied life on and around the wreck, on the wreck large specimens of fish

HISTORY:

The HMS Flint belonged to a group of warships – minesweepers, which after the Second World War the British government sold to Norwegian ship owners. So the Norwegian ship owner Valdemar Skogland from Haugesund bought four disarmed British Isles class minesweepers with the intention of partitioning them into cargo ships. One of these decommissioned minesweepers was built in Quebec, Canada in July 1942 and delivered to the British Navy as the HMS Flint. The renovated ship gained a new name – Argo (international call sign LLOR) and in May 1947 it entered service in the fleet of Skogland’s company. On 30th December 1947, the Argo and its 12 crew members sailed out from Haugesund with a cargo of frozen cod for the long journey to Venice. Arriving safely at its destination, in Venice it unloaded the cod, and was loaded with various vegetables, mainly tomatoes for a new destination – Rijeka, where it would then pick up a cargo of quality wood bound for Oslo. Sailing out from Venice on 26th January 1948, the Argo took a course towards Cape Kamenjak at the southern end of Istria.

At about 2000 hrs. the Argo dropped anchor in a cove near Cape Kamenjak. There was a moderate “jugo” (pronounced “yugo”) wind, and visibility was poor. They spent the night there, because the commander did not dare to sail into Kvarner by night due to the fear of mines. At that time, left over from the Second World War, there were still many minefields in the Adriatic uncleared, especially on the outskirts of Kvarner. Only a few safe navigational corridors were marked with buoys which were not equipped with lights.

The following morning at 0730 hrs. the Argo pulled up its anchor and with a moderate southerly wind continued its journey towards Kvarner. Commander Sigvald Svendsbø decided to continue the journey alone trusting in the sea charts, the instructions for sailing into Kvarnerić and the buoys which marked the navigational corridor. However the commander did not know the fact that many of the buoys had disappeared after being detached after several frequent winter storms. The “jugo” wind continually strengthened, reaching storm force around noon. Visibility was becoming worse.

Just before 1230 hrs. the ship shook with a tremendous explosion and it seemed that the ship broke up and immediately began to sink. When the crew surfaced, there was no trace of the ship. Foam from the refrigeration insulation system was floating all over the surface, obscuring their view. The surviving crew members desperately fought for their lives. Smoke was all around them, and the poisonous gas from the refrigeration system stung their eyes which almost poisoned them. The only option was to swim downwind. After some time they split up. Mikalsen had swum into the cove of Vošćice east of the settlement of Koromačno, on the eastern coast of Istria. When he came round, he saw a light from a nearby house. Early in the morning the police and inhabitants began to search the shore for survivors. They only found small remains of the ship, between which the lifeless bodies of the helmsman Hovland and the sailor Vikingstad were floating.

WRECK CONDITION AND DIVING:

The wreck of the Argo is split into two in the middle. The two parts detached from each other, and both parts lie on the bottom in an upright position. They are connected by a rope so that in poor visibility it is possible to swim from one part of the ship to the other. Visibility depends on the season and daily conditions, and even on the time of day.

As the location is in the open sea the wreck can only be located with the help of GPS equipment and a good echo sounder. Visibility can be quite poor under the surface – in the summer months a murky warm layer of sea may extend down to ten or so metres deep. However visibility in the lower layers is most frequently better. Passing thirty metres the visibility suddenly begins to improve.

Floating above the forecastle we can observe the anchor gear and chains which lead towards the holes in the deck. The anchors are still in place on both sides of the bow. From the forecastle steps lead down to the main deck. On it can be seen the dark opening of the forward cargo hold. Immediately behind the opening is the base of the mast which lies broken next to the wreck. After less than three metres in the direction of the stern, the superstructure and hull suddenly stop – it looks as though some giant had torn away the rest of the ship! At the point of the break the thick plating is torn and twisted in all directions as though it was made of paper. Underneath the deck here it is possible to carefully enter the interior of the ship and there is enough space to pass all the way to the forward cargo hold.

Following the rope we come to the second part of the wreck, about fifty metres away. The rope is tied to the very end of the stern, right next to a small aft superstructure. Passing around the elegantly curved stern we can look for the propeller and rudder blade, however a murky layer of seawater often hangs close to the silty or sandy seabed. Returning to the aft deck and swimming further, we come across the dark opening of the rear cargo hold, and a little further is the rest of the superstructure on the sides of which are attached the davits for the lifeboats. In front of the funnel rectangular upper windows can be seen which served as ventilation for the engine room, some of which are open. Just a few metres further and this section of the wreck abruptly ends at the torn panelling and split hull. At this point for several metres part of the deck is very bent upwards, looking exactly like an opened can of tuna. At the point of the break is looks as though one can peek into the interior, but due to the amount of debris of various pipes, wires and metal plating it is not recommended to linger too long.

The safest way to end the dive and return to the surface is by going back to the part of the ship where the rope is tied, which is also handy to hold on to when the current can be quite strong, whilst we need to perform decompression.

The description and illustrations are a courtesy of Danijel Frka and Jasen Mesić. Buy the whole book here: https://shop.naklada-val.hr/product_info.php?products_id=561

The investment is co-financed by the Republic of Slovenia and the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund.

The investment is co-financed by the Republic of Slovenia and the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund.  H2O Globe BETA

H2O Globe BETA